Physicists would like to understand how elemental materials behave under extreme pressures, several times the pressure found at the Earth’s core. Such understanding could help them to develop materials with new properties, gain insight into the processes going on inside giant planets and stars, and expand their fundamental knowledge of physics. An international team of scientists has taken a step toward achieving those goals by compressing the metal osmium and examining the test material with high-brightness x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne. Their work produced surprising results.

The first surprise was just how stable osmium proved to be. The team of researchers from the University of Bayreuth (Germany), The University of Chicago, the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY, Germany), the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (France), Linköping University (Sweden), CNRS, École Polytechnique (France), Radboud University (The Netherlands), Ural Federal University (Russia), Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the National University of Science and Technology (“MISIS,” Russia) subjected the metal to 770 gigapascals (GPa), the highest static pressure ever achieved. Even at that extreme, the osmium maintained its hexagonal crystalline structure, although the volume of a unit cell—the most basic repeating structure fragment of a crystal—shrank with increasing pressure and the ratio of two parameters of the crystalline lattice grew.

The second surprise came from the fact that there were two anomalies in the readings, the first at approximately 150 GPa and the second at 440 GPa. At those pressures there was a sudden drop in the unit cell parameter ratio, suggesting the material had undergone an electronic transition. Researchers repeated their experiments and determined that the anomalies, though small, were real and not simply experimental artifacts.

The researchers believe that the first anomaly, at 150 GPa, is likely an electronic topological transition related to valence electrons in the outer shell of the atom.

More interesting, and unexpected, was the anomaly at 440 GPa. There, the scientists believe, the cause was a core-crossing transition, a phenomenon they had never observed before.

Generally, in solids, it is the valence electrons that give the material its properties and bond the atoms together. Changes in the structure come when these valence electrons are rearranged. Inner electrons that are closer and more tightly bound to the atomic nucleus in the atom’s core, are not expected to change their state at all. In this experiment, however, core electrons were pushed so close together that their electronic clouds overlapped, and electrons of the states labeled 5p and 4f started to interact.

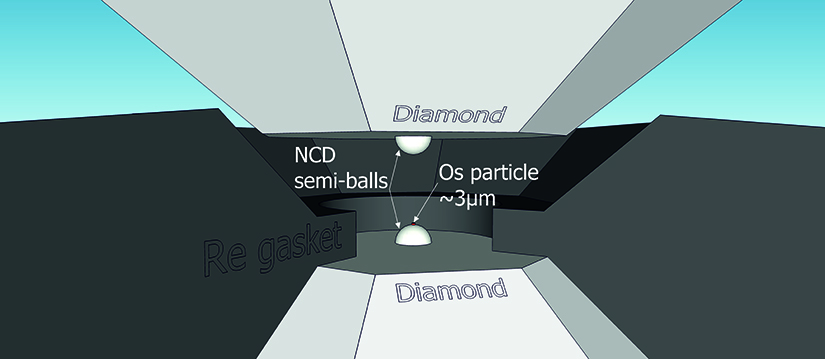

To reach these pressures, the researchers used a device they had developed called a double-stage diamond anvil cell, with second-stage anvils made of nanocrystalline diamond, between which they placed their sample for compression.

The scientists used gold, platinum, and tungsten powders to calibrate their measurements and to make sure they were getting the same readings at different x-ray sources.

The team performed diffraction x-ray measurements to determine the crystal structure of their samples at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS (GSECARS) beamline 13-ID-D at the APS, at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France, and at the Extreme Conditions Beamline P02.2 of PETRA III at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY, Germany). The GSECARS beamline allowed the team to perform the highest-pressure experiments, because it has the narrowest beam of the sources they used, and thus could reach sufficient resolution for the most compressed state of the osmium.

In the future, the researchers hope they can reach even higher pressures, above 1 terapasca (TPa). The processes inside gas giant planets take place at pressures from 1 to 10 TPa.

— Neil Savage

See: L. Dubrovinsky1*, N. Dubrovinskaia1, E. Bykova1, M. Bykov1, V. Prakapenka2, C. Prescher2, K. Glazyrin3, H.-P. Liermann3, M. Hanfland4, M. Ekholm5, Q. Feng5, L.V. Pourovskii5,6, M.I. Katsnelson7,8, J.M.Wills9, and I.A. Abrikosov5,10**, “The most incompressible metal osmium at static pressures above 750 gigapascals,” Nature 525, 226 (2015). DOI: 10.1038/nature14681

Author affiliations: 1University of Bayreuth, 2The University of Chicago, 3Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), 4European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, 5Linköping University, 6CNRS, École Polytechnique, 7Radboud University, 8Ural Federal University, 9Los Alamos National Laboratory, 10National University of Science and Technology “MISIS”

Correspondence: *Leonid.Dubrovinsky@uni-bayreuth.de, **Igor.Abrikosov@ifm.liu.se

L.D. and N.D. acknowledge financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Germany. N.D. thanks the DFG for funding through the Heisenberg Program and the DFG project number DU 954-8/1, and the BMBF for grant number 5K13WC3 (Verbundprojekt O5K2013, Teilprojekt 2, PT-DESY). M.E., Q.F., and I.A.A. acknowledge support fromtheSwedish Foundationfor Strategic Research programme SRL grant numbers 10-0026, the Swedish Research Council (VR) grant numbers 621-2011- 4426, the Swedish Government Strategic Research Area Grant Swedish e-Science Research Centre (SeRC), and in Materials Science ‘‘Advanced Functional Materials’’ (AFM). The work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (grant number 14.Y26.31.0005). The simulations were carried out using supercomputer resources provided by the Swedish national infrastructure for computing (SNIC). M.I.K. acknowledges financial support from the ERC Advanced grant number 338957 FEMTO/NANO and from NWO via a Spinoza Prize. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation-Earth Sciences (EAR-1128799) and U.S. Department of Energy(DOE)-GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.