The formation of dendrites (a crystal or crystalline mass with a branching, treelike structure) is a critical process not only in metallurgy but in other areas of materials science. The specific nature and shapes of dendritic structures affect the properties of metals and other solid materials at the most basic level. Yet many of the details of their formation remain unclear because of technical difficulties that have limited the study of what is essentially a three-dimensional (3-D) phenomenon to only two spatial dimensions, or to the artifacts associated with “quench-and-look” experiments wherein a completely solid sample is analyzed. But experimenters working at X-ray Science Division beamline 2-BM-A,B at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) have extended the study of dendritic morphology into the fourth dimension (three physical dimensions plus time) using a new tomographic reconstruction algorithm with x-ray synchrotron techniques. The work was published in Nature Scientific Reports.

Although previous research has yielded many insights into the ways in which dendritic growth begins and proceeds in a undercooled liquid, such experiments have utilized thin cells and transparent organic materials that provide only a two-dimensional perspective, and one that may not fully translate to metallic dendrites. Techniques that attempt to capture 3-D dendritic formation by quenching an undercooled metallic liquid are less than ideal because they can cause artifacts. And theoretical models are hampered by the lack of actual three-dimensional datasets. Other x-ray studies of metallic dendrites have been limited in either spatial or temporal resolution.

To overcome these problems, the team of researchers from Northwestern University, Purdue University, Carnegie Mellon University, and Argonne used a method called “TIMBIR” (time-interlaced model-based iterative reconstruction), which combines interlaced sampling with a model-based iterative reconstruction approach to achieve x-ray tomographic views with better resolution than previously possible.

Working at the 2-BM beamline of the Argonne APS, an Office of Science user facility, the experimenters studied dendritic growth in a 1-millimeter-diameter sample of Al-24wt%Cu alloy cooled at a rate of 2° C/minute.

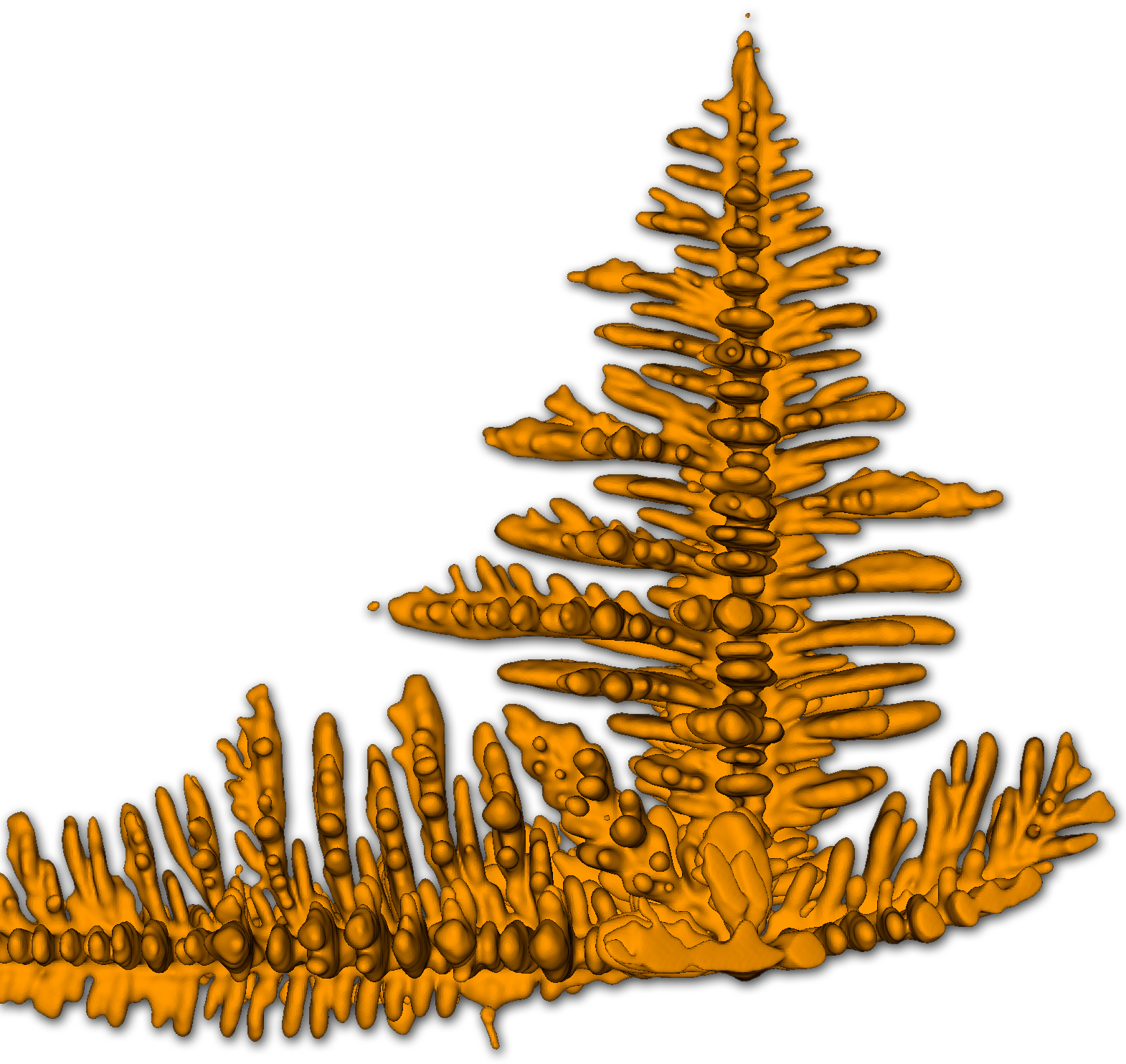

Observing dendritic formation as the sample cooled and solidified (See the figure), the experimenters selected one of the free-growing dendrites for detailed analysis. The usual practice in x-ray microtomography is to acquire a series of images at increasing view angles, which are later reconstructed; but the large number of images required necessitates a certain sacrifice in the temporal frame rate.

The TIMBIR method, however, avoids this pitfall by an interlaced view sampling approach, which distributes the sampled view angles more evenly in time, followed by reconstruction combining both sensor measurements (forward model) and the object (prior model).

While the dendrite tip grew slightly too fast for the 1.8-second time frame of the reconstructions, the side branches grew slowly enough to be easily resolved. Calculating the curvatures of many small areas at once gave an interface shape distribution, from which the overall morphology of the dendrite could be determined, and which also provided crucial data for comparison with dendritic simulations.

The researchers noted that the secondary and tertiary dendritic arms consist of mostly cylindrical patches with spherical caps, with a notable lack of self-similarity with increasing distance from the tip. The arms take on an overall flat and plate-like appearance, unlike dendrites seen in transparent organic materials. The tips of the secondary arms also often undergo splitting as the arms elongate. This phenomenon is also not seen in organic analogs, representing another important difference from metallic dendrites. The liquid trapped in the groove of the split arms prevents further splitting but also can result in a high level of solute segregation.

With the TIMBIR technique, these experiments demonstrate a method for 3-D characterization of metallic dendritic growth that for the first time provides an excellent degree of both spatial and temporal resolution of the free-growth stage. Unlike previous methods, this new approach yields a fresh and detailed quantitative picture of the growth morphology of metallic dendrites that promises to expand the understanding of this vital process and improve the accuracy of theoretical models and simulations. The research team notes that further improvements in the TIMBIR algorithm and camera frame rates will only enhance the resolving power and thus the importance of this novel approach to x-ray tomography.

— Mark Wolverton

See: J.W. Gibbs1, K.A. Mohan2, E.B. Gulsoy1, A.J. Shahani1, X. Xiao3, C.A. Bouman2, M. De Graef4, and P.W. Voorhees1*, “The Three-Dimensional Morphology of Growing Dendrites,” Sci. Rep. 5, 11824 (03 July 2015).| DOI: 10.1038/srep11824

Author affiliations: 1Northwestern University, 2Purdue University, 3Argonne National Laboratory, 4Carnegie Mellon University

Correspondence: * p-voorhees@northwestern.edu

K.A. Mohan, E.B. Gulsoy, A.J. Shahani, C.A. Bouman, M.De Graef, and P.W. Voorhees were supported by an Air Force Office of Scientific Research / Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative grant No. FA9550-12-1-0458. J.W. Gibbs was supported by a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) National Nuclear Security Administration Stewardship Science Graduate Fellowship (grant No. DE-FC52-08NA28752). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.