The powerful blend of fluorescence microscopy with x-ray synchrotron imaging is nothing new.But as some recent experimental work has amply demonstrated, technical advances at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) have greatly enhanced the utility of techniques such as synchrotron-based x-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM). Through increased data acquisition speed, it is now possible to achieve both high spatial resolution and a large field of view at trace-element sensitivity.Two recent studies published in the journal Metallomics highlight the newly-enhanced capabilities of these imaging tools for tasks such as determining the elemental distribution and speciation in biological specimens.

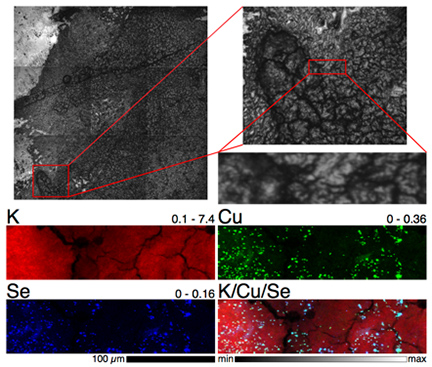

In one study, investigators from the University of Adelaide, the University of Sydney, and Argonne National Laboratory used the Advanced Photon Source, the Australian Synchrotron, and the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource to examine the biological distribution and speciation of selenium and copper in rats fed diets high in selenium.While both selenium and copper are essential elements for life, their actual activity within the body depends upon the particular form of each element, with some forms more efficacious and beneficial than others.

"The (bio)chemistry of these elements is fragile and having to 'prepare' the samples often leads to modification of the properties that we are trying to examine," said study co-author Hugh Harris.By using both XFM and XAS, the researchers could examine the distribution and speciation of selenium and copper in intact tissues from animals exposed to some experimental treatments.

Harris and his colleagues took advantage of the "fly-scanning" mode of XFM recently developed at the APS, an Office of Science user facility, which allows much faster imaging of wider sample areas."Before this, the sample image was built up point by point, stopping at each spot on the sample to collect a spectrum - now the sample keeps moving and the spectrum is collected rapidly on the fly," Harris said. "This allows us to image much larger areas of tissue than we could previously."

Their work at the X-ray Science Division (XSD) 2-ID-E x-ray beamline at the APS revealed a striking correlation between selenium and copper distribution in the kidneys of rats on a 5-ppm selenite diet (see the first figure).While this phenomenon had been identified before in cell cultures, the current work using the XFM/XAS combination allowed this intriguing co-localization of elements to be studied in tissue specimens in vivo for the first time.The team plans to further refine their experimental techniques to study the causes of this unusual co-distribution of elemental concentrations.

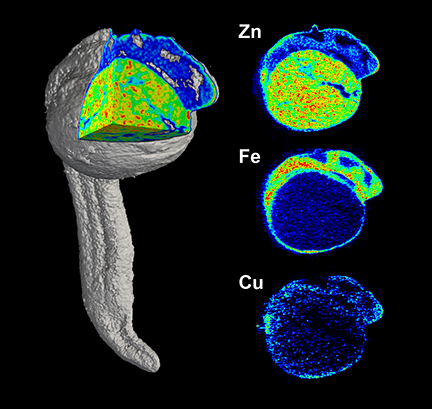

Another notable study, by investigators from the Georgia Institute of Technology, Emory University, Rowiak LaserLabSolutions GmbH, and Argonne employed XFM to delineate elemental distribution of transition metals in the zebrafish embryo.

"The ability of detecting and quantifying trace metal levels within intact biological specimens remains challenging," said Christoph J. Fahrni, co-author of a second article in Metallomics."Compared to other microanalytical techniques, XFM is currently the only available method that is compatible with fully hydrated biological specimens such as whole cells and tissues, while simultaneously offering trace element sensitivity and submicron spatial resolution."

Fahrni and his colleagues also worked at the XSD 2-ID-E beamlineat the APS, using XFM to obtain tomographic images in a zebrafish embryo that was cryogenically preserved at 24 hours post-fertilization in a polymer that was later trimmed away using a femtosecond laser microtome.Sixty tomographic projections were acquired over more than 100 hours of beam time and used to reconstruct the three-dimensional distribution of zinc, copper, and iron in the specimen (see the second figure).

"We made a few unexpected observations regarding the elemental distribution within the embryo," Fahrni said."Perhaps the most striking observation was the markedly increased levels of zinc and copper at the posterior end of the embryo, an area that is involved in progenitor cell differentiation and cellular proliferation and responsible for most of the body growth at this stage of development."

Although the spatial resolution in this specific dataset was not quite sufficient to allow the elemental distribution to be related to specific cell types, the experimenters were able to identify larger anatomical features, including the yolk extension and regions of the brain.

Both groups of researchers were enthusiastic about the results they were able to achieve with the fluorescence microscopy facilities at the APS, and are looking forward to conducting further research.Fahrni said, "With further improved data acquisition times, especially as they might become available with the planned APS Upgrade, it would be possible to perform larger scale comparative studies of organisms."

"There are many other selenium species that are important in the diet or as potential treatments for various diseases and similar work would hopefully yield useful information about their biochemistry," Harris said."The APS is still the world's leading facility for this type of work - we couldn’t complete these studies without access to it and the expertise of its people."— Mark Wolverton

See: Claire M. Weekley1, Anu Shanu2, Jade B. Aitken2, Stefan Vogt3, Paul K. Witting2, and Hugh H. Harris1*, “XAS and XFM studies of selenium and copper speciation and distribution in the kidneys of selenite-supplemented rats,” Metallomics 6, 1602 (2014). DOI: 10.1039/c4mt00088a

Author affiliations: 1The University of Adelaide, 2The University of Sydney, 3Argonne National Laboratory

Correspondence: * hugh.harris@adelaide.edu.au

Part of this research was undertaken at the X-ray Fluorescence Microprobe beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, Victoria, Australia. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program (P41RR001209). Travel funding provided by the International Synchrotron Access Program (ISAP) managed by the Australian Synchrotron and funded by the Australian Government, research funding from the Australian Research Council (DP0985807 to H.H.H.) and the Australian Synchrotron Postgraduate Award (C.M.W.). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

and

See: Daisy Bourassa1, Sophie-Charlotte Gleber2, Stefan Vogt2, Hong Yi3, Fabian Will4, Heiko Richter4, Chong Hyun Shin1, and Christoph J. Fahrni1*, “3D imaging of transition metals in the zebrafish embryo by X-ray fluorescence microtomography,” Metallomics 6, 1648 (2014). DOI: 10.1039/c4mt00121d

Author affiliations: 1Georgia Institute of Technology, 2Argonne National Laboratory, 3Emory University, 4LLS Rowiak LaserLabSolutions GmbH

Correspondence: * fahrni@chemistry.gatech.edu

Financial support by the National Science Foundation (CHE-1306943 to CJF), the National Institutes of Health (K01DK081351 to CHS), and the Vasser Woolley Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.