Certain seismic waves move slower than expected through the Earth’s core, causing researchers to rethink what the innermost region of our planet is made of. One possibility is that the core contains a large amount of carbon. New research on a form of iron-carbide, Fe7C3, shows that it may have the required low seismic wave velocity at high pressure. The experiments, performed at two x-ray beamlines at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), an Office of Science user facility, provide a first-ever estimate of the speed of seismic waves in this iron-carbide at core conditions and suggest that the iron-carbide’s anomalous velocity behavior is due to a change in the electron spin configuration of iron in the material. The results could imply that the Earth’s core is rich in Fe7C3, which might explain where some of Earth’s supposedly “missing carbon” is hiding.

Earthquakes produce seismic waves of two varieties: compression waves (P-waves) and shear waves (S-waves). Observations of waves traversing the center of the Earth have revealed that S-waves arrive much later (with respect to the P-waves) than would be expected for a solid pure-iron core. A potential explanation is that iron in the core is mixed with lighter elements – such as carbon, silicon, or oxygen. Geologists are currently studying different iron alloy candidates to find one that might explain the seismic wave observations.

As far as carbon is concerned, past work looked at the iron-carbide, Fe3C, but recent studies showed that a different iron-carbide, Fe7C3, is more stable at high pressure. A group of researchers from the University of Michigan, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the University of Hawaii at Manoa, the California Institute of Technology, the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and Argonne National Laboratory performed the high-pressure experiments on Fe7C3.

The Fe7C3 samples were synthesized at the University of Michigan and at the GeoSoilEnviroCARS facility at the Argonne APS. The team used the iron isotope 57 because it is a Mössbauer isotope. The nuclear resonance, excited with 14.4-keV x-rays, provided unique information about the valence, spin state, and geometric arrangement of atoms around the iron atom. The team loaded their samples into a diamond anvil cell to apply pressure up to a maximum of 154 GPa and measured the effects of high pressure on Fe7C3 using nuclear resonant inelastic x-ray scattering (NRIXS), which was performed at the X-ray Science Division beamline 3-ID-B,C,D at the APS. This beamline offers tightly-focused synchrotron radiation (with a beam-waist of less than 10 µm) and a small energy bandwidth (1 meV) at the 57Fe resonance of ~14 keV.

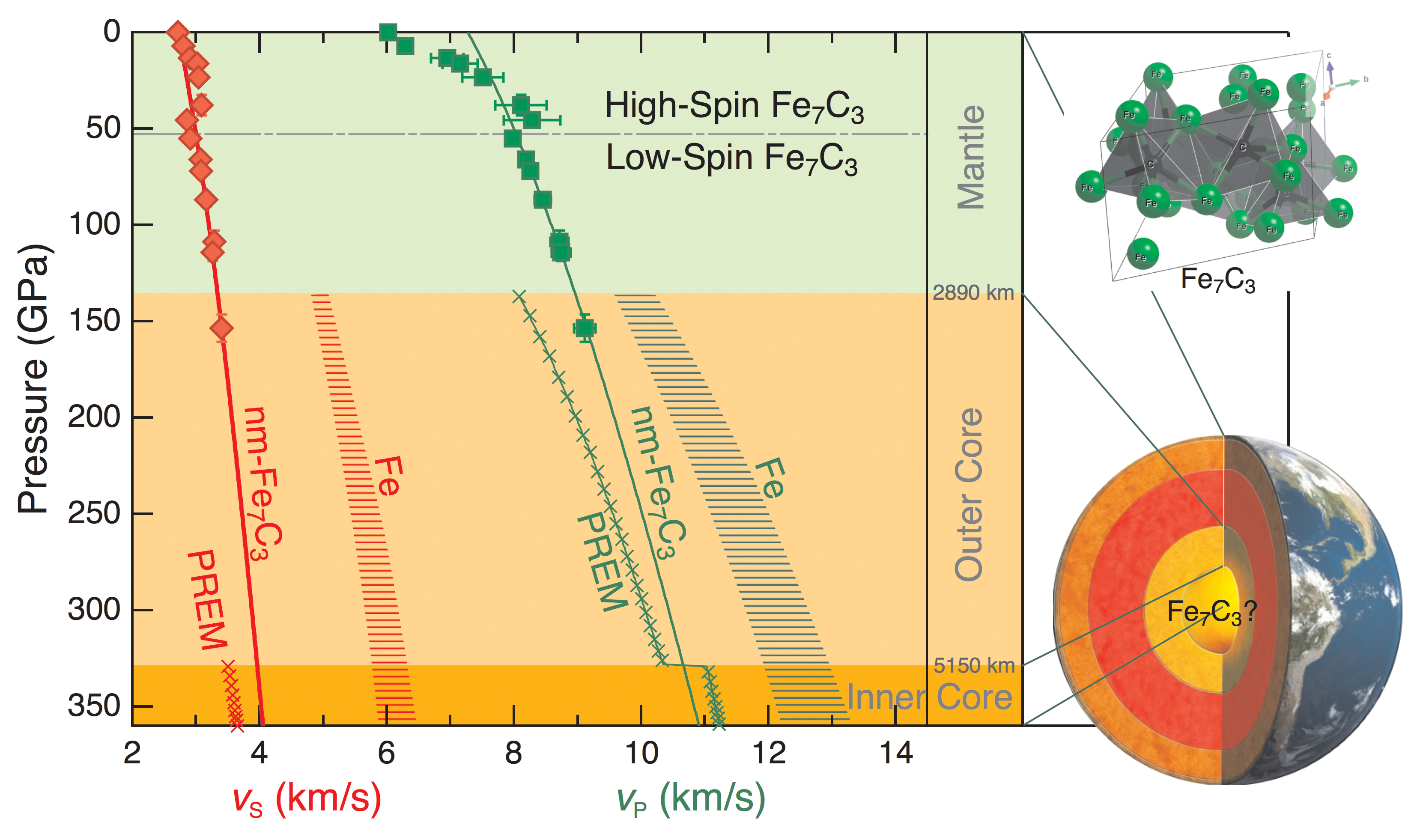

The NRIXS data provided a measurement of the phonon density-of-states, from which the researchers derived the seismic wave velocities for P-waves and S-waves. At low pressures, both velocities increased with pressure, as is usually the case, but near 50 GPa, the S-wave velocity dropped abruptly from 3.1 to 2.8 km/s. Beyond this dip (toward higher pressures) both seismic wave velocities increased, but at a slower rate than before the dip.

The velocity dip corresponds to a spin-pairing transition in Fe7C3 near 50 GPa. In this transition, the electrons in the 3d orbital of iron atoms pair up in a way that lowers the total spin momentum of the atoms. The team explored this transition using x-ray emission spectroscopy at the High Pressure Collaborative Access Team (HP-CAT) 16-ID-D beamline at the APS, as well as synchrotron Mössbauer spectroscopy at the 3-ID-B,C,D beamline. The observations suggested that the paired electrons exert less resistance to shearing, and this “shear softening” may explain why the S-wave velocity remains low above the transition.

When the team extrapolated their results to higher pressure, they found that the S-wave velocity of Fe7C3 at 330 GPa and room temperature was only 14% above the empirically inferred S-wave velocity in the core (Fig. 1). The discrepancy is small enough that it could be explained by a modest temperature-dependence in the seismic wave velocity of Fe7C3. By comparison, pure iron has an S-wave velocity that is 65% above observed values, which is hard to account for without invoking a dramatic temperature-dependence.

One way, therefore, to explain the low S-wave velocity in the core is to assume that it is principally made up of Fe7C3. If such were the case, then the core would contain 60 x 1020 kg of carbon, which is roughly 10 times the current core estimate. That amount of carbon would make the core the largest reservoir of carbon on Earth. Moreover, this could help explain why the carbon abundance is so low — relative to silicon — on the Earth’s surface.

According to this hypothesis, roughly two-thirds of the planet’s carbon inventory is locked in the core — trapped there by its interaction with iron during the formation of the planet.

— Michael Schirber

See: Bin Chen1,2,3*, Zeyu Li1, Dongzhou Zhang4, Jiachao Liu1, Michael Y. Hu5, Jiyong Zhao5, Wenli Bi2,5, E. Ercan Alp5, Yuming Xiao6, Paul Chow6, and Jie Li1**, “Hidden carbon in Earth’s inner core revealed by shear softening in dense Fe7C3,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111(50), 17755 (December 16, 2014). DOI : 10.1073/pnas.1411154111

Author affiliations: 1University of Michigan, 2University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 3University of Hawaii at Manoa, 4California Institute of Technology, 5Argonne National Laboratory, 6Carnegie Institution of Washington

Correspondence: * binchen@hawaii.edu, ** jackieli@umich.edu

This study was supported in part by GSECARS, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF)-Earth Sciences (EAR-1128799) and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)-GeoSciences (DE-FG02-94ER14466). The authors acknowledge support from Grants NSF EAR-1219891, NSF EAR-1023729, NSF INSPIRE AST-1344133, and Carnegie/DOE Alliance Center CI JL 2009-05246. HP-CAT operations are supported by the DOE-National Nuclear Security Administration under Award No. DE-NA0001974 and DOE-Basic Energy Sciences under Award No. DE-FG02-99ER- 45775, with partial instrumentation funding by NSF. B.C. acknowledges support from COMPRES and the University of Hawaii. School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) contribution no. 9228, and the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology (HIGP) contribution no. 2057. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Illustration on APS home page from: https://carnegiescience.edu/sites/carnegiescience.edu/files/EarthPlanOr…