Convection occurs in more places than just the pasta water boiling on your stovetop: it is a key feature of plate tectonics, the large, rigid blocks that comprise the Earth’s crust and mantle. The rising and falling of mantle material tugs the plates along and is apparent to us on the surface as sea floor spreading, volcanism, and earthquakes. However, it is the heat escaping from the Earth's core that powers all these phenomena. Because of the depth of the core — 2900 kilometers below the Earth’s surface — scientists can perform few direct measurements of the core's composition. Current theories postulate the core is mainly composed of iron, nickel, and lighter elements. In new research, including experimentation at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), an international team of scientists has shown it is possible that carbon is one of those lighter elements. They further conclude that, in an environment like that of the Earth's core, carbon significantly modifies the properties of iron, making iron behave with the elasticity of rubber.

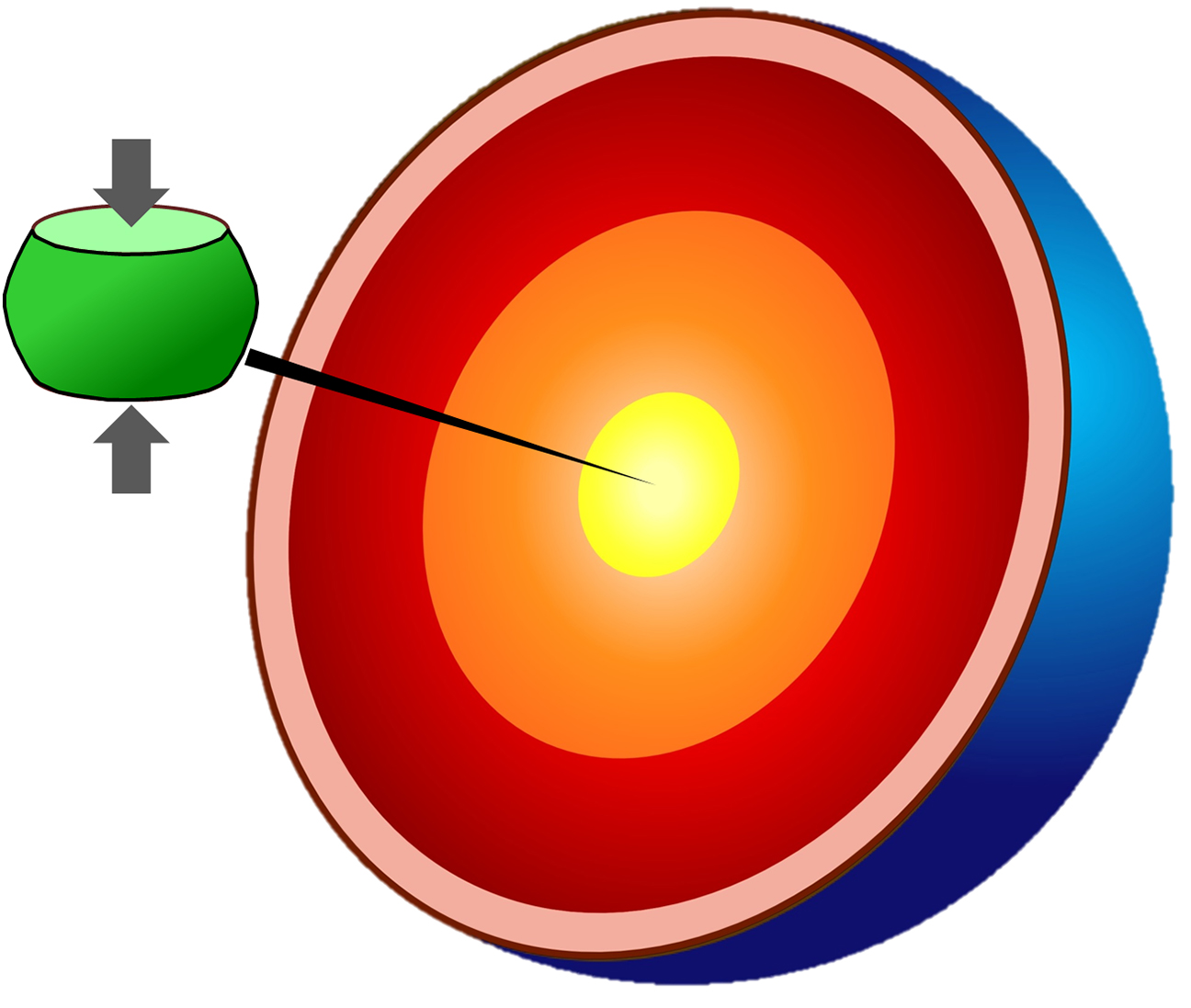

We know from seismological observations that the Earth's core is not purely iron. These measurements give lower values for density and shear wave velocities in the inner core than predicted for pure iron. They also yield higher than expected values for Poisson's ratio (a measure of the deformability/compressibility of a material, as shown in the figure) in the inner core. So scientists have been looking for elements whose presence would give values closer to those measured for these characteristics.

Why try carbon? Previous work had examined an iron carbide phase, Fe3C, with lower shear wave velocities and limited compressibility in response to increasing pressure. So these researchers, from the Universität Bayreuth (Germany), The University of Chicago, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, France), the Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron (Germany), Cornell University, RIKEN SPring-8 Center (Japan), and the National Research Center (Russia) explored the phase stabilities in the iron-carbon system using multi-anvil apparatus.

Thermodynamic predictions proposed that Fe7C3 is the most probable phase at the Earth's inner core conditions. Starting samples of Fe7C3 were synthesized with pressures ranging from 7 GPa to 15 GPa and temperatures between 1473 K and 1973 K. The team was surprised when their single-crystal x-ray diffraction tests showed an orthorhombic structure with space group Pbca — a new form for iron carbide and unlike the structure revealed by previous work on Fe7C3 using powder diffraction. (The previous work showed hexagonal structures or orthorhombic structures with different space groups.)

The team performed a number of tests on this new, orthorhombic crystal, o-Fe7C3, to determine its characteristics at room temperature and pressure as well as under conditions like those in the Earth's core. Working at the GSECARS 13-ID-D beamline at the Argonne APS, they tested the structural stability of o-Fe7C3, utilizing laser-heating and a diamond anvil cell for high-temperature and high-pressure powder x-ray diffraction measurements.

They found that the structure remained the same when the pressure and temperature increased. Additional investigation by transmission electron microscopy on a recovered quenched sample (which had been molten at 205 GPa) showed the same structure as in the low-pressure experiments. This indicates that o-Fe7C3 is in a stable liquidus phase at the conditions in the Earth's core.

The team continued to subject o-Fe7C3 to tests, using single-crystal x-ray diffraction to determine there were no structural phase transitions or changes in compressibility, unlike the previously-studied hexagonal h-Fe7C3.

Since Poisson's ratio depends on pressure, the team examined the vibrational and elastic properties of o-Fe7C3 (to a pressure of approximately 158 GPa) using nuclear inelastic scattering at the ESRF. (Energy-domain synchrotron Mössbauer source spectroscopy was also carried out at the ESRF.) They calculated a value from this data for Poisson's ratio and extrapolated it to the pressure and temperature conditions near the Earth's core. Their resulting value was in good agreement with standard reference models and much closer to those reference values than iron mixtures containing silicon, nickel, or hydrogen. This is more evidence that carbon likely exists in the core.

The results of these laboratory investigations into the properties of iron carbide include not only a new crystal form but also a value for Poisson's ratio much closer to that measured in the Earth's core than that measured for pure iron. The presence of carbon in the core in this form would explain many of the unexpected characteristics provided by seismological data, bringing us one step closer to understanding the heat source that powers plate tectonics.

— Mary Alexandra Agner

See: C. Prescher1,2*, L. Dubrovinsky1, E. Bykova1, I. Kupenko1,3, K. Glazyrin1,4, A. Kantor1,3, C. McCammon1, M. Mookherjee1,5, Y. Nakajima1,6, N. Miyajima1, R. Sinmyo1, V. Cerantola1, N. Dubrovinskaia3, V. Prakapenka2, R. Rüffer3, A. Chumakov3,7, and M. Hanfland3, “High Poisson’s ratio of Earth’s inner core explained by carbon alloying,” Nat. Geoscience 8, 220 ( (March 2015). DOI: 10.1038/NGEO2370

Author affiliation: 1Universität Bayreuth, 2The University of Chicago, 3European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, 4Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron, 5Cornell University, 6RIKEN SPring-8 Center, 7National Research Center “Kurchatov Institut”

Correspondence: *clemens.prescher@gmail.com

Partial financial support was provided through the German Science Foundation (DFG), the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and the PROCOPE exchange programme. GeoSoilEnviroCARS is supported by the National Science Foundation - Earth Sciences (EAR-1128799). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.