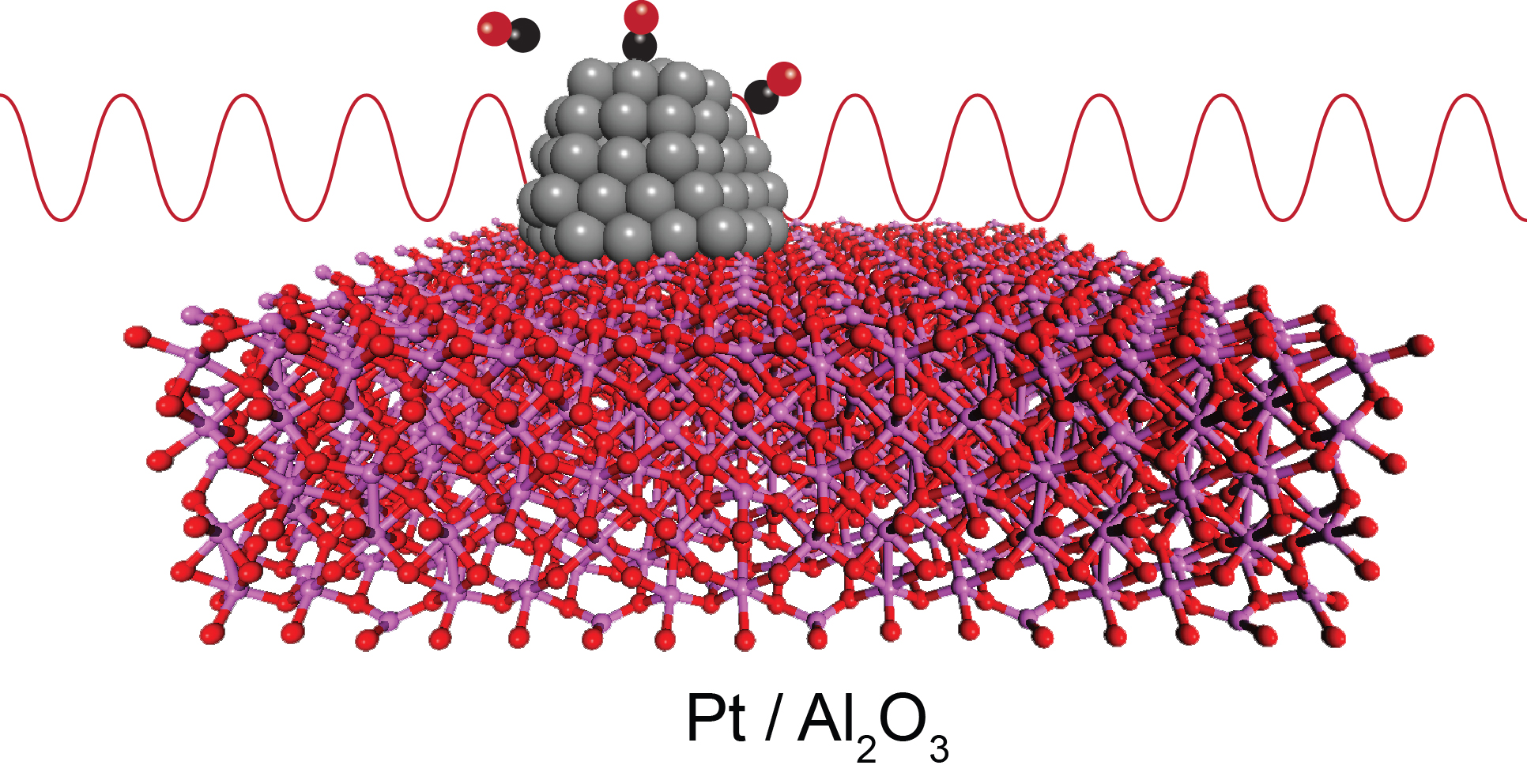

Smaller is better for a metal catalyst, but smaller also means more compact in terms of the metal's atomic structure. Chemical engineers often fabricate metal catalysts in the form of nanoparticles in order to increase their reactive surface area. However, the small size can lead to structural changes in how the metal atoms assemble together. A new suite of x-ray experiments on platinum (Pt) nanoparticles gives the most detailed picture yet of the consequences of going small. Measurements taken at three different x-ray beamlines at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) confirm that atom-spacing becomes smaller as the size of a nanoparticle decreases, but the spacing expands back to near normal when gas molecules adsorb on the surface (first figure). Because this contraction-relaxation affects the way reactants behave on the metal surface, the results of these experiments may help in designing better catalysts.

Platinum, nickel, palladium, and similar metals are used as catalysts in the petroleum and pharmaceutical industries to accelerate organic synthesis, as well as in car exhaust systems to remove toxic fumes. These metals are able to drive reactions by trapping reactants on their surface. Therefore, for a given amount of metal, reaction rates can be increased if the material is divided up into nanoparticles that have a high surface-to-volume ratio.

Earlier x-ray studies suggested that metal nanoparticles are slightly smaller in size than one would expect from the atom-spacing found in normal chunks of metal. One possible explanation for this contraction is that atoms forming the outer surface are pulled inward because they have no neighbors pulling from the other side. Previous experiments have found evidence for this model, but scientists would still like to understand precisely how the surface atoms behave in different circumstances.

Scientists at the Argonne and Brookhaven National Laboratories, the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Kansas State University, and Purdue University performed both x-ray scattering and spectroscopy measurements on Pt nanoparticles. The results were reported in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

The team began by growing Pt nanoparticles on powder grains of alumina (Al2O3). A powder substrate like this is often used for industrial catalysts. However, the researchers used a special atomic layer deposition process that controlled the size of the Pt nanoparticles by varying the number of deposition cycles. Three separate samples were produced with nanoparticle widths of 1, 2, and 3 nanometers, as measured through small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) at the X-ray Science Division (XSD) 12-ID-B x-ray beamline at the Argonne APS, an Office of Science user facility.

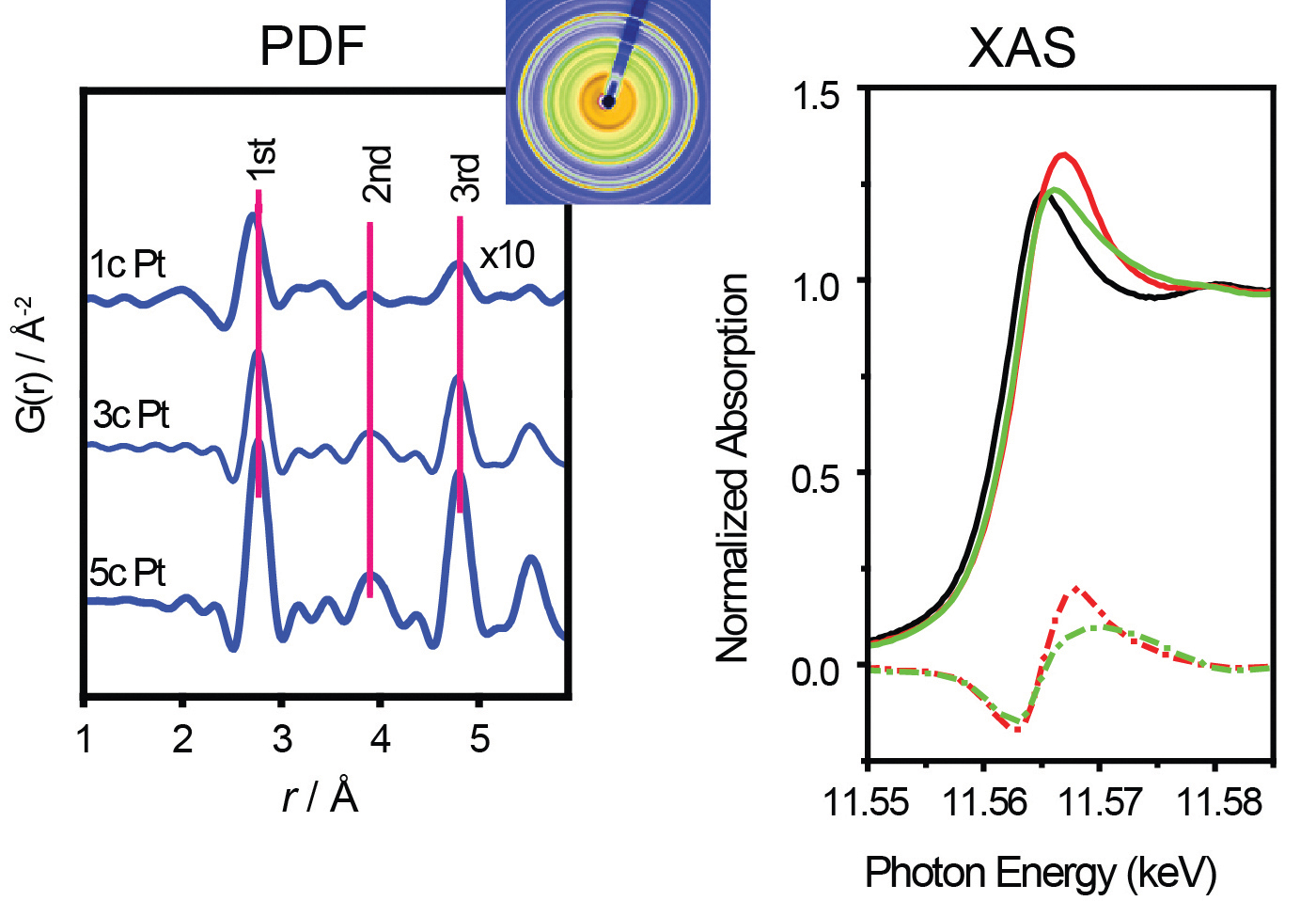

The prepared samples were next placed in the XSD beamline 11-ID-B, where total scattering measurements revealed typical atom separations as represented by the pair distribution function (PDF, left in second figure).

The sample chamber was initially filled with helium gas, which doesn't absorb on platinum. In this “bare surface” case, the atomic separations for 1-nanometer-wide Pt particles were on average 1.4% smaller than those in normal bulk metal. Similar contraction was observed – but to a lesser degree – for the bigger nanoparticles in the other two samples.

However, during catalysis, the nanoparticle surfaces will not be bare. To explore this, the team first injected hydrogen gas (H2) into the sample chamber. The hydrogen adsorbed on the platinum, exemplifying the typical reduction step in a catalytic cycle. Afterwards, the team purged the system and introduced carbon monoxide (CO), which represents the complementary oxidation step in a catalytic cycle.

For both gas exposures, x-ray scattering measurements showed that the adsorption caused the nanoparticles to expand from their contracted bare surface state. However, the amount of expansion was not the same in the two cases. Nanoparticles with CO on their surfaces had slightly larger interatomic separations than nanoparticles with H2 adsorption.

To understand the chemical bond behavior during this contraction and expansion, the researchers performed x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) at the 10-BM beamline of the Materials Research Collaborative Access Team (MR-CAT) at the APS (right in second figure).

The nanoparticles exhibited different absorption spectra, depending on whether the surrounding gas was helium, hydrogen or carbon monoxide. The largest spectral differences occurred for the 1-nanometer-wide sample, which suggests that smaller nanoparticles form stronger bonds with the adsorbed gas molecules.

Such quantitative information could be useful in designing catalysts, since engineers want a material that can hold reactants on its surface, but not too strongly. Finding the right balance may simply be a question of sizing up nanoparticles.

— Michael Schirber

See: Yu Lei2, Haiyan Zhao1, Rosa Diaz Rivas3, Sungsik Lee1, Bin Liu4, Junling Lu1, Eric Stach3, Randall E. Winans1, Karena W. Chapman1, Jeffrey P. Greeley5, Jeffrey T. Miller1, Peter J. Chupas1, and Jeffrey W. Elam1*, “Adsorbate-Induced Structural Changes in 1−3 nm Platinum Nanoparticles,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9320 (2014). DOI: 10.1021/ja4126998

Author affiliations: 1Argonne National Laboratory, 2University of Alabama in Huntsville, 3Brookhaven National Laboratory, 4Kansas State University, 5Purdue University

Correspondence: * jelam@anl.gov

This material is based upon work supported as part of the Institute for Atom-efficient Chemical Transformations, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science - Basic Energy Sciences. MR-CAT operations are supported by the Department of Energy and the MR-CAT member institutions. Y.L. gratefully acknowledges the start-up support by the University of Alabama in Huntsville. B.L. also thanks the start-up support by the Kansas State University. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.