Perovskites — any material with the same structure as calcium titanium oxide (CaTiO3) —continue to entice materials scientists with their ferroelectricity, ferromagnetism, catalytic activity, and oxygen-ion conductivity. In recent years, scientists realized that they could vastly improve the properties of perovskites by assembling them into thin films. The problem was that no one understood why thin films beat out bulk materials.

Researchers gained new insight into thin-film superiority by probing the structure of perovskites at the X-ray Science Division 33-ID-D,E x-ray beamline at the U.S. Department of Energy's Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory. They used a groundbreaking approach to tease apart the thin-film structure and chemistry layer-by-layer.

As the researchers peeled back the layers, they found that, instead of having a uniform distribution of elements, there were drastic differences in composition between the thin-film layers. This observation may help researchers design thin-film perovskites with enhanced activity and stability.

Industrial applications for perovskites, which efficiently reduce oxygen, include the conversion of energy from fossil fuels to electricity, oxygen purification, and electrocatalysis. The research team, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Hebrew University (Israel), Argonne National Laboratory, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory studied LSCO thin films — perovskites made from lanthanum, strontium, cobalt, and oxygen (LSCO) — as a model system for studying why thin films have greater reducing power than their bulk counterparts.

The researchers studied two 4-nm LSCO thin films at the APS, a DOE Office of Science user facility; one annealed thin film had been previously heated to 550° C for one hour to simulate real-world industrial settings, while the other as-deposited thin film was left at ambient temperatures.

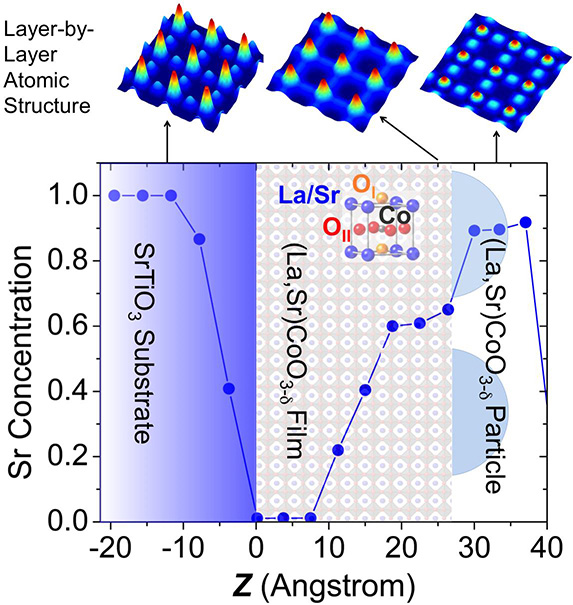

The researchers then collected diffraction intensities along 10 different reciprocal space objects, called "Bragg rods," defined by the substrate. They used Coherent Bragg Rod Analysis (COBRA) to determine the three-dimensional (3-D) atomic structure of each thin-film layer, with higher peaks in the map indicating an element with a greater number of electrons, allowing the researchers to differentiate elements at different sites within the LSCO thin films.

But COBRA alone does not give information about the distribution of elements that occupy the same atomic site within the layers. Therefore, the researchers applied a second method called "energy differential COBRA," namely, performing COBRA measurements along Bragg rods by varying the incident x-ray energies around the strontium K-edge at each reciprocal space point. This approach provided the absolute strontium occupation fraction in a layer-by-layer fashion.

The end result of combining conventional COBRA with energy differential COBRA was high-resolution (sub-angstrom) 3-D atomic images of the LSCO thin films that included information about elemental distribution.

The 3-D atomic images clearly showed that strontium tended to cluster in the outer layers of the LSCO thin films, while lanthanum filled those positions in the deeper layers of the film. Strontium is almost entirely absent in the thin-film layers closest to the substrate.

The researchers suspect that surface strontium segregation observed in the LSCO thin films may explain why they outperform bulk materials. Lanthanum and strontium have different charges, such that if a layer has more strontium, it must also have less oxygen, or more oxygen vacancies. A dearth of oxygen in a thin-film outer layer, where strontium was found to be plentiful, means that the material may have more opportunities to react with oxygen at its surface, explaining the enhanced performance.

The structure and chemistry of the annealed and as-deposited thin films were similar, suggesting that heat itself does not alter the material's structure or activity. In future experiments, the researchers will study thin films subjected to harsher real-world conditions. They also aim to use the insights gained at the Advanced Photon Source to design better perovskite materials in the future.

— Erika Gebel Berg

See: Zhenxing Feng1, Yizhak Yacoby2, Wesley T. Hong1, Hua Zhou3, Michael D. Biegalski4, Hans M. Christen4, and Yang Shao-Horn1*, "Revealing the atomic structure and strontium distribution in nanometer-thick La0.8Sr0.2CoO3_δ grown on (001)-oriented SrTiO3," Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 1166 (2014). DOI:10.1039/c3ee43164a

Author affiliations: 1Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2Hebrew University, 3Argonne National Laboratory, 4Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Correspondence: * shaohorn@mit.edu

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Energy (SISGR DESC0002633) and King Abdullah University of Science and Technology. The authors thank the King Fahd University of Petroleum (KFUPM) and Minerals in Dharam, Saudi Arabia, for funding the research reported in this paper through the Center for Clean Water and Clean Energy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and KFUPM. The PLD preparation performed was conducted at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is sponsored at Oak Ridge National Laboratory by the Scientific User Facilities Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation under grant no. 1005/11.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.