To fully understand something, it is often instructive to view it at its extremes. How do materials behave when their bits are forced much closer together than is comfortable? How do electrons accommodate proximity? What normal behaviors break down?

The highest pressure a nuclear submarine can safely experience is around 850 lbs per sq in. (psi), or nearly 6 million Pascals (Pa). Pressure washers spew out water at roughly five times this pressure, or 30 million Pa. Three-hundred miles below the surface of the Earth, in a part of the mantle called the transition zone, minerals are squeezed at an immense 15-billion Pa — enough to turn carbon into diamonds.

This is the kind of intense environment that researchers working at the X-ray Science Division 4-ID-D x-ray beamline at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE's) Advanced Photon Source (APS) at the DOE's Argonne National Laboratory applied to GdSi, a compound of gadolinium (Gd) and silicon (Si).

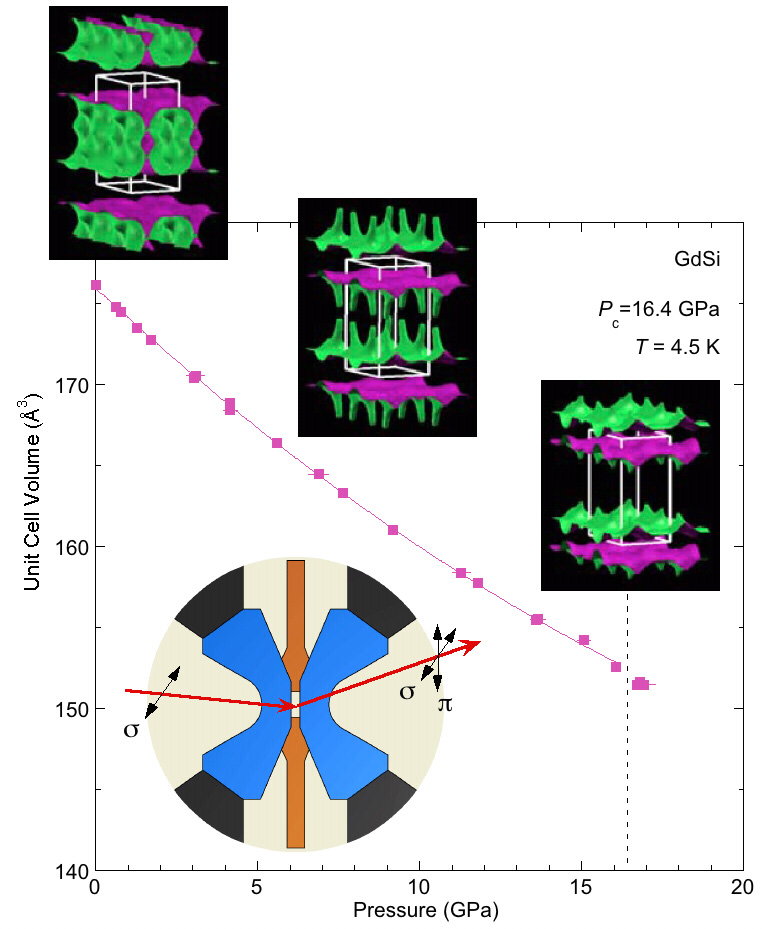

While a diamond anvil cell bore down on the crystalline fleck, x-rays penetrated within, bouncing off of, ejecting, and energizing the material's component parts, and relaying back to the researchers information about the locations and states of its atoms and electrons.

Despite shrinking by one-seventh of its volume, the team discovered that GdSi's magnetism remained robust. This behavior was surprising. High pressure will often quench a magnet. But here, the electrons responded to the harsh conditions by forming a resilient superstructure —ideal behavior for digital memory that needs to withstand abuse.

Some computer memory is based on a concept called "giant magnetoresistance." These devices consist of thin, alternating layers of magnetic and non-magnetic material. The materials interact such that changes in magnetic attraction and repulsion of one layer affect the electrical resistance in the next. Small magnetic fluctuations can create large electronic variations. In this way, digital information can be stored: electric signals change the characteristics of the magnetic material. When the user wants that information back, the magnetic material changes electron flow in the adjacent non-magnetic layer, and the digital information is read back out.

One of the challenges with memory storage is stability. Sometimes the thin layers of material do not match up, and this causes great internal stress. Heat adds another layer of instability. If these stresses change the magnetic material, information is lost. A material like GdSi, which retains its magnetism despite great stress, could make for very stable memory storage.

But what causes this behavior? It can be traced, in part, to a cooperative interaction between mobile electrons and localized spins. With high-sensitivity x-ray diffraction, the researchers examined both the atomic structure and the magnetic state of the GdSi crystal as it was squeezed from all sides (see the figure). Until recently, such direct magnetic tracking was nearly impossible and in fact, this is the first successful use of x-ray magnetic diffraction at such high pressures.

Previously, researchers had to rely on more indirect methods. Now, utilizing the high-brightness x-rays from the APS, a DOE Office of Science user facility, they could "watch" how the magnetic states evolved and compare their observations with theoretical calculations. Previous work had shown that these interactions should stabilize GdSi's magnetism, but now the researchers were able to prove that these effects remained under high pressure.

With experimentally sourced lattice information, the researchers in this study, from Argonne; The University of Chicago; DOE's Los Alamos National Laboratory; the National Science Foundation; the University of Tennessee, Knoxville; and DOE's Oak Ridge National Laboratory then calculated the structure of GdSi's electronic energy bands — the ranges of energy that an electron within the material may assume. These energy bands depend on many factors, including the location of atomic species, as well as the long-range atomic patterns.

The researchers found that through the entire pressure range one dominant band flattened yet still persisted. This continuity likely benefited from the material's stable atomic structure — Gd atoms in hexagonal sheets, layered to form tubes surrounding paired Si atoms, a linear arrangement that translated into robust electronic bands. Each is connected: the lattice created a stable electron band, which together with stable local spins helped to maintain the material's robust magnetism despite immense pressure.

The interplay between electron spin, charge, and atomic arrangement is complex and not always fully understood. GdSi clearly has potential as a material well-suited to computer memory and magnetic sensors but beyond this, the ability to observe how a material's magnetic properties change under extreme conditions should promote more discoveries. Researchers now have a new window into the complex lives of electrons under stress. — Jenny Morber

See: Yejun Feng1, 2*, Jiyang Wang2, A. Palmer2, J.A. Aguiar3, B. Mihaila4, J.-Q. Yan5,6, P.B. Littlewood2,1, and T.F. Rosenbaum2**, "Hidden one-dimensional spin modulation in a three-dimensional metal," Nat. Commun. 5, 4218 (2014). DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5218

Author affiliations: 1Argonne National Laboratory; 2The University of Chicago; 3Los Alamos National Laboratory; 4National Science Foundation; 5University of Tennessee, Knoxville; 6Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Correspondence: * yejun@aps.anl.gov, ** t-rosenbaum@uchicago.edu

P.B.L. was supported by DOE-BES by the Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. B.M. was supported in part by the U.S. DOE under the LANL-LDRD program. A.P was supported in part by DOE-SCGF under Contract No. DEAC05-06OR23100.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.