Understanding how cracks spread through a material is important for predicting how long a structure might last before breaking, as well as for designing new materials more resistant to failure. Researchers have long been able to watch a crack spread along a surface, but because cracks propagate in three dimensions (3-D), such two-dimensional (2-D) studies missed crucial information. Some 3-D methods use x-rays or electron beams to characterize the structure of the cracked crystals that make up the material, but these tend to study only a portion of a crack and typically have no information about its 3-D evolution over time. Now researchers using the high-brightness, highly penetrating x-rays from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source have combined experimental methods to obtain high-resolution, quantitative measurements of the events involved in material cracking, and link the measurements to a history of how a crack evolved.

The cracks in question are “microstructurally small,” meaning that their dimensions are on the order of the grain size in a crystalline material, and that their growth is sensitive to the crystalline structure; the way local grains respond to forces at the leading edge of the crack will determine the next step in the crack’s evolution. The researchers — from Cornell University, Carnegie Mellon University, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory — studied an aluminum-magnesium-silicon alloy used as a liner in a container that stores pressurized fluids.

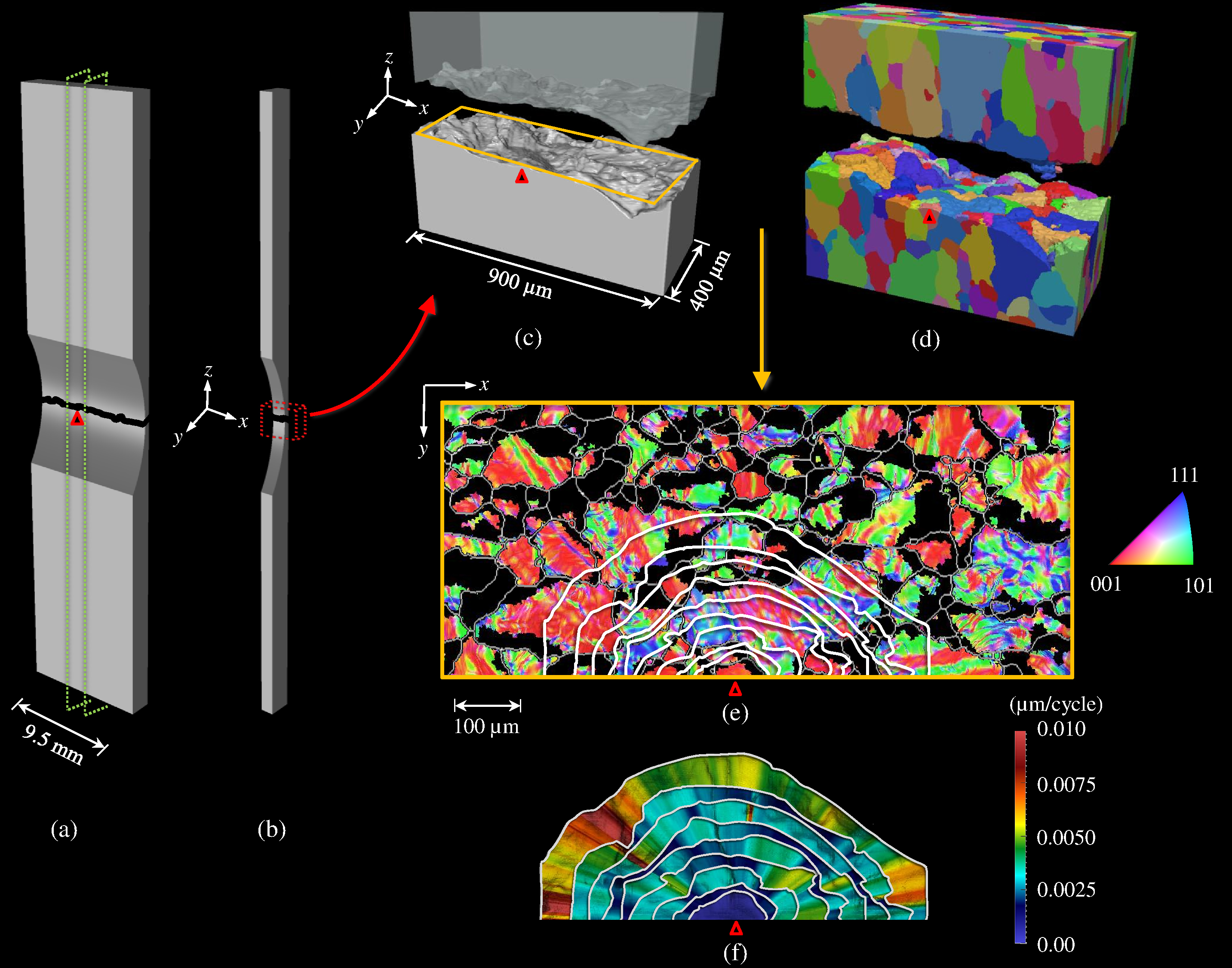

They started by taking a small sample of the alloy, 9.5 mm x 44.5 mm x 1.75 mm with a region in the center milled down to a thickness of 400 µm, where they hoped a crack would form. They alternately applied and released tension to the sample, generating a series of marker bands that let them calibrate how the crack grew over time. They periodically imaged the sample using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to see how far the crack had spread on the visible surface. Once the sample broke in two, they used the marker bands and SEM images to map the crack history and trace the crack to the site where it originated.

Next, they bonded the two halves back-to-back for ease of imaging and mounted the sample at the X-ray Science Division 1-ID beamline at the Argonne National Laboratory Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science user facility. They performed x-ray computed tomography (CT), taking approximately 900 tomograms as they rotated the sample 180°, then stacked the 2-D images together to reconstruct 3-D images of the exposed crack surfaces.

The team also used the beamline to perform near-field, high-energy x-ray diffraction microscopy (HEDM). That technique yielded 3-D maps of the grain shapes and orientations, letting the researchers see whether the crack had grown within grains or along boundaries between grains.

Combining the fracture map, the x-ray CT, and the HEDM provided an unprecedented view of crack evolution from a “naturally” initiated crack (see the figure).

The collected data can now be used to run a computer simulation of cracking, which will help scientists learn what factors control a crack’s evolution in 3-D. They may discover, for example, how big a crack has to grow before forces acting on the bulk of a material become more important than the local microstructure in directing the fracture.

The researchers would like to validate their findings with other aluminum alloys, as well as with other materials, though in some it may be difficult to create the marker bands. There is still much to learn about microstructurally small cracks, the researchers say, but the fact that the APS beamline enables 3-D studies of materials that are actually used in real engineering applications could advance the science significantly.— Neil Savage

See: Ashley D. Spear1,‡,*, Shiu Fai Li2, Jonathan F. Lind3, Robert M. Suter3, and Anthony R. Ingraffea1, “Three-dimensional characterization of microstructurally small fatigue-crack evolution using quantitative fractography combined with post-mortem X-ray tomography and high-energy X-ray diffraction microscopy,” Acta Mater. 76, 413 (2014). DOI: 10.1016/j.actamat.2014.05.021

Author affiliations: 1Cornell University, 2Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 3Carnegie Mellon University. ‡Present address: University of Utah

Correspondence: * ashley.spear@utah.edu

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-0707428; under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under contract DE-AC52-07NA27344; and by grant DESC0002001 at Carnegie Mellon University. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.