Important new information about the way melanoma cancer cells fight for their lives has been uncovered by researchers from the National Cancer Institute and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory. This discovery could help improve current therapeutic approaches to stopping this pernicious disease.

The malignant skin tumors known as melanomas are highly curable in the early stages of development. But once melanoma spreads throughout the body, chances for a cure are greatly reduced. And the possibility of melanoma spreading is high, as this is one of the most aggressive forms of cancer. The number of melanomas is increasing rapidly and now ranks fifth among the most common cancers in the United States. It is estimated that, in 2006, there will be ~62,000 new diagnoses of melanoma and ~7,900 fatalities in the U.S. alone.

A major obstacle in treating melanomas is that they are resistant to radiation therapy as well as many chemotherapeutic drugs. These drugs act on DNA, on microtubules (protein structures that assist in nuclear division, form the cell plate, and provide a framework for cell wall establishment), and on topoisomerases, the enzymes that act on the topology of DNA. Unraveling the cellular mechanisms of drug resistance in melanomas is a key to halting this deadly intruder as it attempts to spread from cell to cell.

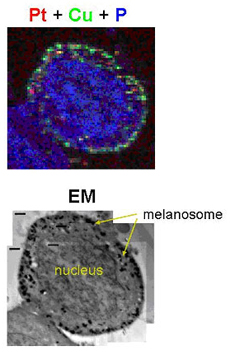

Using the fluorescence microprobe at the X-ray Operations and Research 2-ID-D beamline at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Photon Source at Argonne, the researchers have shown how cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatium), a common chemotherapeutic drug, is contained within cells. Although cisplatin has been designed with fluorescent “labels” attached to allow tracking with conventional optical microscopes, these fluorescent molecules may affect the cellular properties of the drug or create misleading artifacts. The x-ray fluorescence technique bypasses this drawback by providing direct imaging of the unmodified drug inside cells.

The results of this research showed that cisplatin was initially sequestered in melanosomes, a unique membrane-bound organelle found in pigmented cells that protect melanocytes against the harmful effects of toxic intermediates produced during melanin synthesis. This led to a drastic reduction in nuclear accumulation of cisplatin ― and also a reduction in DNA damage ― in melanoma cells compared with control cells from a non-melanoma skin cancer cell line.

Thus intracellular melanosomal drug trapping, and subsequent active melanosome-mediated drug export, may prove to be the multidrug resistance mechanisms underlying the intractability of malignant melanomas. This suggests that multiple components of the melanogenic pathway could become molecular therapeutic targets for increasing the chemosensitivity of melanoma cells.

Contact: Michael M. Gottesman, mgottesman@nih.gov.

See: Kevin G. Chen, Julio C. Valencia, Barry Lai, Guofeng Zhang, Jill K. Paterson, Francois Rouzaud, Werner Berens, Stephen M. Wincovitch, Susan H. Garfield, Richard D. Leapman, Vincent J. Hearing, Michael M. Gottesman, "Melanosomal sequestration of cytotoxic drugs contributes to the intractability of malignant melanomas," Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 (26), 9903-9907 (2006). doi:10.1073/pnas.0600213103

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Dept. of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38.

Argonne National Laboratory is a U.S. Department of Energy laboratory managed by The University of Chicago