Many important things happen at interfaces — adsorption, corrosion, and catalysis, to name just a few. Understanding how such processes operate is of critical importance in many areas, ranging from geochemistry to physics, but observing phenomena at such tiny scales isn’t easy. Conventional techniques such as electron and atomic force microscopy and optical interferometry all have inherent limitations, whether it’s the need for a vacuum environment, penetrating power, the use of an invasive and possibly reactive probe tip, or others that compromise the resolution and quality of the observations. And x-ray microscopy (XRM) is hampered by its resolving power of about 10-20 nanometers.

All this is a big problem for interfacial science, where the reactivity depends on the topography, such as the distribution of steps and terraces at subnanometer scales. Without the ability to make direct observations at the molecular level, interfacial scientists have been limited to broad descriptions and generalized averaging approaches that can only approximate what’s really happening. Is there a better way? Can molecular-scale features be effectively imaged somehow using current microscopic methods?

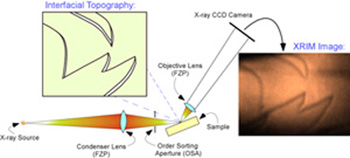

A team from Argonne and Xradia, Inc. has found a solution by developing a novel form of XRM: reflecting x-rays off a surface and using phase contrast of the reflected rays to detect monomolecular steps in the (001) surface of orthoclase. For the first time, the technique gives XRM the ability to observe subnanometer features that are smaller than the optical resolution of the x-ray microscope — in this case, approximately 300 times smaller.

“All XRM work to date has been centered on getting as small a focus spot as possible or the best resolution possible and then looking at objects that are that size or bigger,” explains team leader Paul Fenter. “The state of the art in terms of resolution is approximately 20 nm. That effectively restricts x-ray microscopy from looking at any molecular-scale phenomena, which is important for many areas of study. You ultimately want to be able to see the fundamental response of a material as layers are added or removed.”

The team’s x-ray reflection interface microscope (XRIM) uses a monochromatic x-ray undulator beam from the XOR/BESSRC 12-ID-D beamline at the U.S. Department of Energy's Advanced Photon Source at Argonne, focused by a condenser Fresnel zone plate (FZP) lens onto the sample surface. Reflected x-rays are magnified by another FZP lens into a charge-coupled device camera to obtain images in a full field imaging mode. The differences in vertical topography across the surface are indicated by changes in the reflected intensity across the image due to phase contrast, revealing the locations of individual steps. Fenter elaborates, “We’re not seeing the atomic structure of the step, but we can see the step itself. That’s an important advance for interfacial science, because interfacial reactivity is often controlled by steps, which tend to be more reactive.”

The team’s XRIM thus enhances and expands the traditional capabilities of XRM. “This changes the way the XRM community can move forward,” says Fenter. “It extends the reach of what you can look at to a much smaller length scale, down to molecular scale features.”

A key inspiration of Fenter’s team was the insight that, even though the portion of the x-ray beam that is reflected by the interface is perhaps only a millionth of the incident beam, the intensity reduction of x-rays reflected from the monomolecular steps with respect to other parts of the surface is still sufficiently large to allow the subnanometer steps to be detected, and enough to compensate for the weak surface x-ray reflectivity.

Even so, an extremely bright and strong x-ray source is needed for the technique, and the team found the APS, the brightest x-ray source in the Western Hemisphere, to be the perfect tool for their work. “This experiment really requires the full capabilities of the APS,” Fenter points out.

Now that Fenter’s team has proven the feasibility of the technique, what’s the next step? “Our goal is to apply this technique to look at the liquid-solid interface where there are many processes that are difficult to observe with traditional techniques,” Fenter says. “We’re trying to move to a point where we can observe interfacial reactivity under liquids.” Other possible applications include probing interfacial processes that have never before been accessible to direct observation, including buried interfaces, and observing processes including ion adsorption, corrosion, catalytic reactions, particle nucleation, and the formation and switching of ferromagnetic domains.

The team is confident that their XRIM technique will prove to be a valuable addition to the imaging arsenal of interfacial chemists and physicists. Fenter says, “We’ve taken the first baby steps, and we’d like to bring it to the point where it becomes a standard technique for probing interfaces.”

— Mark Wolverton

Contact: *fenter@anl.gov

See: Paul Fenter*, Changyong Park, Zhan Zhang, and Steve Wang, “Observation of subnanometre-high surface topography with x-ray reflection phase-contrast microscopy,” Nat. Phys. 2, 700 (October 2006). DOI: 10.1038/nphys419

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences, Geosciences Research Program through contract DE-AC02-06CH11357 to Argonne National Laboratory. XOR/BESSRC at the APS is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Argonne is a U.S. Department of Energy Laboratory managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC