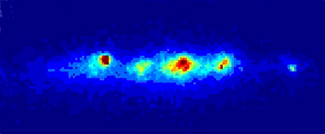

Due to their unique structural properties, metals are ubiquitous in every-day life and of central importance for competitive industries such as aviation and automobile manufacturing. The deformation behavior of metals is critical to the forming and eventual failure of components. Under deformation, metals gain strength by accumulating linear defects in a complex internal structure. Despite decades of research, the underlying physical processes that lead to the dislocation structure formation are still not well understood. Crystalline materials such as pure copper are built of nearly perfectly ordered grains separated by walls that are highly distorted. Stresses such as pulling on either side of a metal cause irreversible or plastic deformation that ripples through the crystalline lattice, causing accumulation of dislocations in some regions of the grains but not in others. Using copper as a test case, researchers from Risø National Laboratory and Argonne employed a novel experimental technique at XOR beamline 1-ID to demonstrate that the formation of dislocation structure in a macroscopic sample can be observed during deformation. With hard x-rays, a series of “snapshots” of defect patterns were taken and essentially undistorted islands within individual deformed grains identified. It was discovered that these islands emerge and disappear during deformation, thus providing revolutionary microscopic insight into the collective behavior of defects under load. Such data provide decisive tests of advanced models of the strength of materials.

Contact: Henning Friis Poulsen (Risø National Laboratory) henning.friis.poulsen@risoe.dk

See: Bo Jakobsen et al., “Formation and Subdivision of Deformation Structures During plastic Deformation,” Science 312 (5775) 889-892 (12 May 2006) doi: 10.1126/ science.1124141

See also: MATERIALS SCIENCE: Collective Defect Behavior under Stress

By Ladislas Kubin

When a piece of material is bowed or bent, it may deform in an irreversible, or plastic, manner. This property is useful to metallurgists in two ways. First, it may be used to process metallic ingots into various types of products. Second, when submitted to an overload in service conditions, materials may gently deform plastically rather than breaking abruptly. For decades, materials scientists have longed for dynamic insights into the microscopic events associated with plastic flow. On page 889 of this issue [of Science], Jakobsen et al. (1) report an important step in this direction. READ MORE

This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation and the Danish Natural Science Research Council. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38

Argonne National Laboratory is a U.S. Department of Energy laboratory managed by The University of Chicago